Pigment has the staying power of shrapnel; it indelibly marks the inflicted observer, searing into his consciousness.

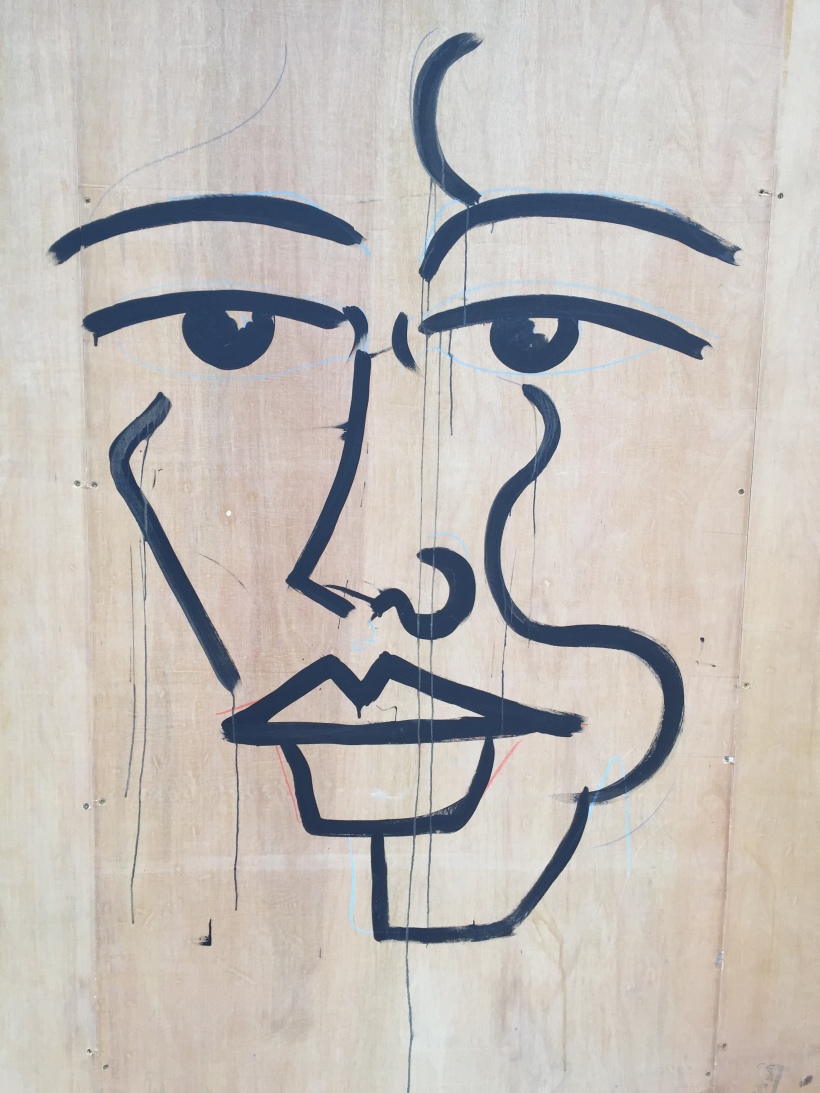

Chronicling the vast cultural shifts in America, Raymond Pettibon (b. 1957), via means of pen and paintbrush, has captured the collapse of the American counterculture into the factious political present. A wordsmith, documentarian, artist, and satirist, Pettibon has achieved international recognition for rendering universal critiques in a deeply personal manner. His witty, widely disseminated attacks on political figures—Reagan, Bush, Kennedy, and more recently Trump—magnify the public’s murmured complaints. Juxtaposing borrowed text with both original and found drawing, Pettibon creates in response to the present geo-political landscape.

Complicating interpretation, Pettibon’s works are often oblique references; they demand the viewer’s complete engagement; they must be textually decoded. Yet, this process of decipherment may not lead to greater clarity. Alas, the greater intention, which the viewer ardently seeks to read into the work, may remain an enigma. However, it is the inherent contradictions, the gaps in concrete meaning, in Pettibon’s art that visually proclaim the absurdity of American culture and politics since 1960. The stylistic tropes and phrases Pettibon employs express the body politics’ confused, despairing response to the tribulations of America since 1960: America’s shifting values, elected politicians’ personal blunders, and military miscalculations.

Displaying over 800 of Pettibon’s zines, sketchbooks, self-portraits, political satires, and surf scenes, the New Museum has devoted three floors to an artist retrospective. The exhibition, “Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work,” which, remarkably, is the artist’s first retrospective in New York, can be viewed until April 9, 2017.

Image: Raymond Pettibon, No Title, (I spent ayll…), 2016.